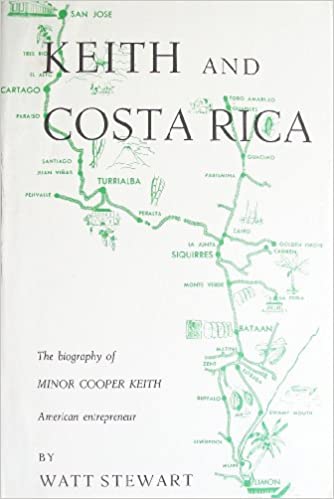

At the time, Costa Rica's economy was based primarily on the export of coffee, which was grown in the country's central valley and transported by oxcart to the Pacific port of Puntarenas. Since the main market for Costa Rican coffee was in Europe and no canal connecting the Pacific and the Atlantic existed, creating a reliable transportation route to the Caribbean was a priority for the Costa Rican government and business class.

The construction of that railroad proved extraordinarily challenging due to inadequate financing, compounded by the rugged terrain, thick jungle, torrential rains, and prevalence of malaria, yellow fever, dysentery, and other tropical diseases. As many as four thousand people, including Keith's three brothers, died during the construction of the first 25 miles of track, mostly from malaria.

Keith was forced to hire foreign laborers, including black workers from Jamaica, as well as some Chinese and even Italians. The Jamaicans that Keith brought in were English speakers and to this day maintain their heritage.

He also recruited prisoners, and guaranteed them a pardon after the railroad was completed, but of the 700 that signed on to help, only 25 survived the work, diseases, etc.

By 1882, the Costa Rican government had defaulted on its payments to Keith and could no longer meet its obligations to the London banks from which it had borrowed to pay for the railroad. Keith managed to raise £1.2 million himself from the banks and from private investors. He also negotiated a substantial reduction of the interest on the money previously lent to Costa Rica, from 7% to 2.5%. In exchange, the government of President Próspero Fernández Oreamuno gave Keith 800,000 acres (324,000 hectares) of tax-free land along the railroad, plus a 99-year lease on the operation of the train route.

These terms were made official in a document signed by Keith and cabinet minister Bernardo Soto Alfaro on April 21, 1884 (known to Costa Rican historians as the "Soto-Keith contract"). That land grant corresponded to about 6% of the total territory of Costa Rica.

The railroad was completed in 1890, but the flow of passengers and cargo proved insufficient to finance Keith's debt. As early as 1873, however, Keith had begun experimenting with the planting of bananas, grown from roots he had obtained from the French. To market the bananas, Keith began running a steamboat line from Limón to New Orleans, in the United States.

The resulting banana trade proved lucrative and he soon established the Tropical Trading and Transport Company to organize his banana-export business.

Keith then partnered with M. T. Snyder to establish banana plantations in Panama and in Colombia's Magdalena Department. He eventually came to dominate the banana trade in Central America and Colombia.

In 1899, he was forced by a financial setback to combine his venture with Andrew W. Preston's Boston Fruit Company, which dominated the banana trade in the West Indies. The result of the merger was the powerful United Fruit Company, of which Keith became vice-president. In 1904, Keith signed a contract with the President of Guatemala, Manuel Estrada Cabrera, giving the company tax-exemptions, land grants, and control of all railroads on the Atlantic side of the country.

Keith was a trustee of the foundation that managed George Gustav Heye's collection of Native American artifacts and he bequeathed his own ancient Native American gold to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

The Brooklyn Museum is preparing to return about 4,500 pre-Columbian artifacts taken from Costa Rica roughly a century ago.

Costa Rica had made no claim to the objects, which were exported in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by Minor C. Keith, a railroad magnate and a founder of the United Fruit Company. And there were none of the conflicts, legal threats or philosophical debates that sometimes accompany arguments between museums and countries that claim ownership of antiquities in their collections.

Instead, the museum simply decided that its closets were too full, overstuffed with items acquired during an era when it aimed to become the biggest museum in the world. So it offered the pieces to the National Museum of Costa Rica, which accepted but has yet to raise the $59,000 needed to pack and ship the first batch.

The objects that the Brooklyn Museum plans to let go are primarily made of ceramic and stone; they include bowls and other vessels, figurines, benches and ceremonial metates, or grinding stones. They are among 16,000 artifacts, some made of gold and jade, that Keith and his workers found on his Costa Rican banana plantations.

The museum plans to keep some of the most valuable pieces, including gold and jade animals and anthropomorphic figurines and pendants. It is unlikely that many of the items being returned have ever been exhibited

The museum acquired the Keith collection in 1934, five years after Keith’s death. Keith, who was born in Brooklyn, had gone to Costa Rica in 1871, at 23, to join his brother in building a railroad from San José to the Caribbean Sea. During the project’s construction — which took two decades — Keith also established himself as one of the biggest growers and exporters of bananas in Central America. It was on one of his Costa Rican plantations, called Las Mercedes, that his workers first came across pre-Columbian gold ornaments, spurring the start of his collecting.

Ms. Quirós said there were no legal issues surrounding the Brooklyn Museum’s ownership of the objects, since they left the country before a 1938 Costa Rican law restricting export of archaeological artifacts.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minor_Cooper_Keith

https://www.npr.org/transcripts/794302086

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/01/arts/design/01costa.html

https://www.library.hbs.edu/hc/pc/large/united-fruit.html

https://www.prints-online.com/limon-costa-rica-united-fruit-company-offices-11553386.html#modalClose

http://costaricarailroad.blogspot.com/2008/10/chronology-of-railroad-in-costa-rica.html

History of which I had no knowledge. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteVery informative,thank you sir.Found this;

ReplyDeletehttps://youtu.be/yKEqU5qNPMI

you're welcome, and thank you! I'll add that video to the post!

Delete